The Arguments Usually Alleged in Support of Free Will Refuted:

1. Enough would seem to have been said on the subject of man's will, were there not some who endeavour to urge him to his ruin by a false opinion of liberty, and at the same time, in order to support their own opinion, assail ours. First, they gather together some absurd inferences, by which they endeavour to bring odium upon our doctrine, as if it were abhorrent to common sense, and then they oppose it with certain passages of Scripture, (infra, sec. 6.) Both devices we shall dispose of in their order. If sin, say they, is necessary, it ceases to be sin; if it is voluntary, it may be avoided. Such, too, were the weapons with which Pelagius assailed Augustine. But we are unwilling to crush them by the weight of his name, until we have satisfactorily disposed of the objections themselves. I deny, therefore, that sin ought to be the less imputed because it is necessary; and, on the other hand, I deny the inference, that sin may be avoided because it is voluntary. If any one will dispute with God, and endeavour to evade his judgement, by pretending that he could not have done otherwise, the answer already given is sufficient, that it is owing not to creation, but the corruption of nature, that man has become the slave of sin, and can will nothing but evil. For whence that impotence of which the wicked so readily avail themselves as an excuse, but just because Adam voluntarily subjected himself to the tyranny of the devil? Hence the corruption by which we are held bound as with chains, originated in the first man's revolt from his Maker. If all men are justly held guilty of this revolt, let them not think themselves excused by a necessity in which they see the clearest cause of their condemnation. But this I have fully explained above; and in the case of the devil himself, have given an example of one who sins not less voluntarily that he sins necessarily. I have also shown, in the case of the elect angels, that though their will cannot decline from good, it does not therefore cease to be will. This Bernard shrewdly explains when he says, (Serm. 81, in Cantica,) that we are the more miserable in this, that the necessity is voluntary; and yet this necessity so binds us who are subject to it, that we are the slaves of sin, as we have already observed. The second step in the reasoning is vicious, because it leaps from voluntary to free; whereas we have proved above, that a thing may be done voluntarily, though not subject to free choice.

2. They add, that unless virtue and vice proceed from free choice, it is absurd either to punish man or reward him. Although this argument is taken from Aristotle, I admit that it is also used by Chrysostom and Jerome. Jerome, however, does not disguise that it was familiar to the Pelagians. He even quotes their words, "If grace acts in us, grace, and not we who do the work, will be crowned," (Heron. in Ep. ad Ctesiphont. et Dialog. 1) With regard to punishment, I answer, that it is properly inflicted on those by whom the guilt is contracted. What matters it whether you sin with a free or an enslaved judgement, so long as you sin voluntarily, especially when man is proved to be a sinner because he is under the bondage of sin? In regard to the rewards of righteousness, is there any great absurdity in acknowledging that they depend on the kindness of God rather than our own merits? How often do we meet in Augustine with this expression, - "God crowns not our merits but his own gifts; and the name of reward is given not to what is due to our merits, but to the recompense of grace previously bestowed?" Some seem to think there is acuteness in the remark, that there is no place at all for the mind, if good works do not spring from free will as their proper source; but in thinking this so very unreasonable they are widely mistaken. Augustine does not hesitate uniformly to describe as necessary the very thing which they count it impious to acknowledge. Thus he asks, "What is human merit? He who came to bestow not due recompense but free grace, though himself free from sin, and the giver of freedom, found all men sinners," (Augustin. in Psa 31.) Again, "If you are to receive your due, you must be punished. What then is done? God has not rendered you due punishment, but bestows upon you unmerited grace. If you wish to be an alien from grace, boast your merits," (in Psa 70.) Again, "You are nothing in yourself, sin is yours, merit God's. Punishment is your due; and when the reward shall come, God shall crown his own gifts, not your merits," (Ep. 52.) To the same effect he elsewhere says, (De Verb. Apostol. Serm. 15,) that grace is not of merit, but merit of grace. And shortly after he concludes, that God by his gifts anticipates all our merit, that he may thereby manifest his own merit, and give what is absolutely free, because he sees nothing in us that can be a ground of salvation. But why extend the list of quotations, when similar sentiments are ever and anon recurring in his works? The abettors of this error would see a still better refutation of it, if they would attend to the source from which the apostle derives the glory of the saints, - "Moreover, whom he did predestinate, them he also called; and whom he called, them he also justified; and whom he justified, them he also glorified," (Rom 8:30.) On what ground, then, the apostle being judge, (2Ti 4:8,) are believers crowned? Because by the mercy of God, not their own exertions, they are predestinated, called, and justified. Away, then, with the vain fear, that unless free will stand, there will no longer be any merit! It is most foolish to take alarm, and recoil from that which Scripture inculcates. "If thou didst receive it, why dost thou glory as if thou hadst not received it?" (1Co 4:7.) You see how every thing is denied to free will, for the very purpose of leaving no room for merit. And yet, as the beneficence and liberality of God are manifold and inexhaustible, the grace which he bestows upon us, inasmuch as he makes it our own, he recompenses as if the virtuous acts were our own.

3. But it is added, in terms which seem to be borrowed from Chrysostom, (Homil. 22, in Genes.,) that if our will possesses not the power of choosing good or evil, all who are partakers of the same nature must be alike good or alike bad. A sentiment akin to this occurs in the work De Vocatione Gentium, (lib. 4 c. 4,) usually attributed to Ambrose, in which it is argued, that no one would ever decline from faith, did not the grace of God leave us in a mutable state. It is strange that such men should have so blundered. How did it fail to occur to Chrysostom, that it is divine election which distinguishes among men? We have not the least hesitation to admit what Paul strenuously maintains, that all, without exception, are depraved and given over to wickedness; but at the same time we add, that through the mercy of God all do not continue in wickedness. Therefore, while we all labour naturally under the same disease, those only recover health to whom the Lord is pleased to put forth his healing hand. The others whom, in just judgement, he passes over, pine and rot away till they are consumed. And this is the only reason why some persevere to the end, and others, after beginning their course, fall away. Perseverance is the gift of God, which he does not lavish promiscuously on all, but imparts to whom he pleases. If it is asked how the difference arises - why some steadily persevere, and others prove deficient in steadfastness, we can give no other reason than that the Lord, by his mighty power, strengthens and sustains the former, so that they perish not, while he does not furnish the same assistance to the latter, but leaves them to be monuments of instability.

4. Still it is insisted, that exhortations are vain, warnings superfluous, and rebukes absurd, if the sinner possesses not the power to obey. When similar objections were urged against Augustine, he was obliged to write his book, De Correptione et Gratia, where he has fully disposed of them. The substance of his answer to his opponents is this: "O, man! learn from the precept what you ought to do; learn from correction, that it is your own fault you have not the power; and learn in prayer, whence it is that you may receive the power." Very similar is the argument of his book, De Spiritu et Litera, in which he shows that God does not measure the precepts of his law by human strength, but, after ordering what is right, freely bestows on his elect the power of fulfilling it. The subject, indeed, does not require a long discussion. For we are not singular in our doctrine, but have Christ and all his apostles with us. Let our opponents, then, consider how they are to come off victorious in a contest which they wage with such antagonists. Christ declares, "without me ye can do nothing," (John 20:5.) Does he the less censure and chastise those who, without him, did wickedly? Does he the less exhort every man to be intent on good works? How severely does Paul inveigh against the Corinthians for want of charity, (1Co 3:3;) and yet at the same time, he prays that charity may be given them by the Lord. In the Epistle to the Romans, he declares that "it is not of him that willeth, nor of him that runneth, but of God that showeth mercy," (Rom 9:16.) Still he ceases not to warn, exhort, and rebuke them. Why then do they not expostulate with God for making sport with men, by demanding of them things which he alone can give, and chastising them for faults committed through want of his grace? Why do they not admonish Paul to spare those who have it not in their power to will or to run, unless the mercy of God, which has forsaken them, precede? As if the doctrine were not founded on the strongest reason - reason which no serious inquirer can fail to perceive. The extent to which doctrine, and exhortation, and rebuke, are in themselves able to change the mind, is indicated by Paul when he says, "Neither is he that planteth any thing, neither he that watereth; but God that giveth the increase," (1Co3:7 ) in like manner, we see that Moses delivers the precepts of the Law under a heavy sanction, and that the prophets strongly urge and threaten transgressors though they at the same time confess, that men are wise only when an understanding heart is given them; that it is the proper work of God to circumcise the heart, and to change it from stone into flesh; to write his law on their inward parts; in short, to renew souls so as to give efficacy to doctrine.

5. What purpose, the n, is served by exhortations? It is this: As the wicked, with obstinate heart, despise them, they will be a testimony against them when they stand at the judgement-seat of God; nay, they even now strike and lash their consciences. For, however they may petulantly deride, they cannot disapprove them. But what, you will ask, can a miserable mortal do, when softness of heart, which is necessary to obedience, is denied him? I ask, in reply, Why have recourse to evasion, since hardness of heart cannot be imputed to any but the sinner himself? The ungodly, though they would gladly evade the divine admonitions, are forced, whether they will or not, to feel their power. But their chief use is to be seen in the case of believers, in whom the Lord, while he always acts by his Spirit, also omits not the instrumentality of his word, but employs it, and not without effect. Let this, then, be a standing truth, that the whole strength of the godly consists in the grace of God, according to the words of the prophet, "I will give them one heart, and I will put a new spirit within you; and I will take the stony heart out of their flesh, and will give them an heart of flesh, that they may walk in my statutes," (Eze 11:19,20.) But it will be asked, why are they now admonished of their duty, and not rather left to the guidance of the Spirit? Why are they urged with exhortations when they cannot hasten any faster than the Spirit impels them? and why are they chastised, if at any time they go astray, seeing that this is caused by the necessary infirmity of the flesh? "O, man! who art thou that replies against God?" If, in order to prepare us for the grace which enables us to obey exhortation, God sees meet to employ exhortation, what is there in such an arrangement for you to carp and scoff at? Had exhortations and reprimands no other profit with the godly than to convince them of sin, they could not be deemed altogether useless. Now, when, by the Spirit of God acting within, they have the effect of inflaming their desire of good, of arousing them from lethargy, of destroying the pleasure and honeyed sweetness of sin, making it hateful and loathsome, who will presume to cavil at them as superfluous? Should any one wish a clearer reply, let him take the following: - God works in his elect in two ways: inwardly, by his Spirit; outwardly, by his Word. By his Spirit illuminating their minds, and training their hearts to the practice of righteousness, he makes them new creatures, while, by his Word, he stimulates them to long and seek for this renovation. In both, he exerts the might of his hand in proportion to the measure in which he dispenses them. The Word, when addressed to the reprobate, though not effectual for their amendment, has another use. It urges their consciences now, and will render them more inexcusable on the day of judgement. Thus, our Saviour, while declaring that none can come to him but those whom the Father draws, and that the elect come after they have heard and learned of the Father, (John 6:44,45,) does not lay aside the office of teacher, but carefully invites those who must be taught inwardly by the Spirit before they can make any profit. The reprobate, again, are admonished by Paul, that the doctrine is not in vain; because, while it is in them a savour of death unto death, it is still a sweet savour unto God, (2Co 2:16.)

6. The enemies of this doctrine are at great pains in collecting passages of Scripture, as if, unable to accomplish any thing by their weight, they were to overwhelm us by their number. But as in battle, when it is come to close quarters, an unwarlike multitude, how great soever the pomp and show they make, give way after a few blows, and take to flight, so we shall have little difficulty here in disposing of our opponents and their host. All the passages which they pervert in opposing us are very similar in their import; and hence, when they are arranged under their proper heads, one answer will suffice for several; it is not necessary to give a separate consideration to each. Precepts seem to be regarded as their stronghold. These they think so accommodated to our abilities, as to make it follow as a matter of course, that whatever they enjoin we are able to perform. Accordingly, they run over all the precepts, and by them fix the measure of our power. For, say they, when God enjoins meekness, submission, love, chastity, piety, and holiness, and when he forbids anger, pride, theft, uncleanness, idolatry, and the like, he either mocks us, or only requires things which are in our power. All the precepts which they thus heap together may be divided into three classes. Some enjoin a first conversion unto God, others speak simply of the observance of the law, and others inculcate perseverance in the grace which has been received. We shall first treat of precepts in general, and then proceed to consider each separate class. That the abilities of man are equal to the precepts of the divine law, has long been a common idea, and has some show of plausibility. It is founded, however, on the grossest ignorance of the law. Those who deem it a kind of sacrilege to say, that the observance of the law is impossible, insist, as their strongest argument, that, if it is so, the Law has been given in vain, (infra, Chap. 7 sec. 5.) For they speak just as if Paul had never said anything about the Law. But what, pray, is meant by saying, that the Law "was added because of transgressions;" "by the law is the knowledge of sin;" "I had not known sin but by the law;" "the law entered that the offence might abound?" (Gal 3:19; Rom 3:20; 7:7; 5:20.) Is it meant that the Law was to be limited to our strength, lest it should be given in vain? Is it not rather meant that it was placed far above us, in order to convince us of our utter feebleness? Paul indeed declares, that charity is the end and fulfilling of the Law, (1Ti 1:5.) But when he prays that the minds of the Thessalonians may be filled with it, he clearly enough acknowledges that the Law sounds in our ears without profit, if God do not implant it thoroughly in our hearts, (1Th 3:12.)

7. I admit, indeed, that if the Scripture taught nothing else on the subject than that the Law is a rule of life by which we ought to regulate our pursuits, I should at once assent to their opinion; but since it carefully and clearly explains that the use of the Law is manifold, the proper course is to learn from that explanation what the power of the Law is in man. In regard to the present question, while it explains what our duty is it teaches that the power of obeying it is derived from the goodness of God, and it accordingly urges us to pray that this power may be given us. If there were merely a command and no promise, it would be necessary to try whether our strength were sufficient to fulfill the command; but since promises are annexed, which proclaim not only that aid, but that our whole power is derived from divine grace, they at the same time abundantly testify that we are not only unequal to the observance of the Law, but mere fools in regard to it. Therefore, let us hear no more of a proportion between our ability and the divine precepts, as if the Lord had accommodated the standard of justice which he was to give in the Law to our feeble capacities. We should rather gather from the promises hove ill provided we are, having in everything so much need of grace. But say they, Who will believe that the Lord designed his Law for blocks and stones? There is no wish to make any one believe this. The ungodly are neither blocks nor stones, when, taught by the Law that their lusts are offensive to God, they are proved guilty by their own confession; nor are the godly blocks or stones, when admonished of their powerlessness, they take refuge in grace. To this effect are the pithy sayings of Augustine, "God orders what we cannot do, that we may know what we ought to ask of him. There is a great utility in precepts, if all that is given to free will is to do greater honour to divine grace. Faith acquires what the Law requires; nay, the Law requires, in order that faith may acquire what is thus required; nay, more, God demands of us faith itself, and finds not what he thus demands, until by giving he makes it possible to find it." Again, he says, "Let God give what he orders, and order what he wills."

8. This will be more clearly seen by again attending to the three classes of precepts to which we above referred. Both in the Law and in the Prophets, God repeatedly calls upon us to turn to him. But, on the other hand, a prophet exclaims, "Turn thou me, and I shall be turned; for thou art the Lord my God. Surely after that I was turned, I repented." He orders us to circumcise the foreskins of our hearts; but Moses declares, that that circumcision is made by his own hand. In many passages he demands a new heart, but in others he declares that he gives it. As Augustine says, "What God promises, we ourselves do not through choice or nature, but he himself does by grace." The same observation is made, when, in enumerating the rules of Tichonius, he states the third in effect to be - that we distinguish carefully between the Law and the promises, or between the commands and grace, (Augustin. de Doctrine Christiana, lib. 3.) Let them now go and gather from precepts what man's power of obedience is, when they would destroy the divine grace by which the precepts themselves are accomplished. The precepts of the second class are simply those which enjoin us to worship God, to obey and adhere to his will, to do his pleasure, and follow his teaching. But innumerable passages testify that every degree of purity, piety, holiness, and justices which we possess, is his gift. Of the third class of precepts is the exhortation of Paul and Barnabas to the proselytes, as recorded by Luke; they "persuaded them to continue in the grace of God," (Acts 13:43.) But the source from which this power of continuance must be sought is elsewhere explained by Paul, when he says, "Finally, my brethren, be strong in the Lord," (Eph 6:10.) In another passage he says, "Grieve not the Holy Spirit of God, whereby ye are sealed unto the day of redemption," (Eph 4:30.) But as the thing here enjoined could not be performed by man, he prays in behalf of the Thessalonians, that God would count them "worthy of this calling, and fulfil all the good pleasure of his goodness, and the work of faith with power," (2Th 1:11.) In the same way, in the Second Epistle to the Corinthians, when treating of alms, he repeatedly commends their good and pious inclination. A little farther on, however, he exclaims, "Thanks be to God, which put the same earnest care into the heart of Titus for you. For indeed he accepted the exhortation," (2Co 8:16,17.) If Titus could not even perform the office of being a mouth to exhort others, except in so far as God suggested, how could the others have been voluntary agents in acting, if the Lord Jesus had not directed their hearts?

9. Some, who would be thought more acute, endeavour to evade all these passages, by the quibble, that there is nothing to hinder us from contributing our part, while God, at the same time, supplies our deficiencies. They, moreover, adduce passages from the Prophets, in which the work of our conversion seems to be shared between God and ourselves; "Turn ye unto me, saith the Lord of hosts, and I will turn unto you, saith the Lord of hosts," (Zec 1:3.) The kind of assistance which God gives us has been shown above, (sect. 7, 8,) and need not now be repeated. One thing only I ask to be conceded to me, that it is vain to think we have a power of fulfilling the Law, merely because we are enjoined to obey it. Since, in order to our fulfilling the divine precepts, the grace of the Lawgiver is both necessary, and has been promised to us, this much at least is clear, that more is demanded of us than we are able to pay. Nor can any cavil evade the declaration in Jeremiah, that the covenant which God made with his ancient people was broken, because it was only of the letter - that to make it effectual, it was necessary for the Spirit to interpose and train the heart to obedience, (Jer 31:32.) The opinion we now combat is not aided by the words, "Turn unto me, and I will turn unto you." The turning there spoken of is not that by which God renews the heart unto repentance; but that in which, by bestowing prosperity, he manifests his kindness and favour, just in the same way as he sometimes expresses his displeasure by sending adversity. The people complaining under the many calamities which befell them, that they were forsaken by God, he answers, that his kindness would not fail them, if they would return to a right course, and to himself, the standard of righteousness. The passage, therefore, is wrested from its proper meaning when it is made to countenance the idea that the work of conversion is divided between God and man, (supra, Chap. 2 sec. 27.) We have only glanced briefly at this subject, as the proper place for it will occur when we come to treat of the Law, (Chap. 7 sec. 2 and 3.)

10. The second class of objections is akin to the former. They allege the promises in which the Lord makes a paction with our will. Such are the following: "Seek good, and not evil, that ye may live," (Amo 5:14.) "If ye be willing and obedient, ye shall eat the good of the land: but if ye refuse and rebel, ye shall be devoured with the sword; for the mouth of the Lord has spoken it," (Isaiah 1:19,20.) "If thou wilt put away thine abominations out of my sight, then thou shalt not remove," (Jer 4:1.) "It shall come to pass, if thou shalt hearken diligently unto the voice of the Lord thy God, to observe and do all the commandments which I command thee this days that the Lord thy God will set thee on high above all nations of the earth," (Deu 28:1.) There are other similar passages, (Lev 26:3, &c.) They think that the blessings contained in these promises are offered to our will absurdly and in mockery, if it is not in our power to secure or reject them. It is, indeed, an easy matter to indulge in declamatory complaint on this subject, to say that we are cruelly mocked by the Lord, when he declares that his kindness depends on our wills if we are not masters of our wills - that it would be a strange liberality on the part of God to set his blessings before us, while we have no power of enjoying them, - a strange certainty of promises, which, to prevent their ever being fulfilled, are made to depend on an impossibility. Of promises of this description, which have a condition annexed to them, we shall elsewhere speak, and make it plain that there is nothing absurd in the impossible fulfilment of them. In regard to the matter in hand, I deny that God cruelly mocks us when he invites us to merit blessings which he knows we are altogether unable to merit. The promises being offered alike to believers and to the ungodly, have their use in regard to both. As God by his precepts stings the consciences of the ungodly, so as to prevent them from enjoying their sins while they have no remembrance of his judgements, so, in his promises, he in a manner takes them to witness how unworthy they are of his kindness. Who can deny that it is most just and most becoming in God to do good to those who worship him, and to punish with due severity those who despise his majesty? God, therefore, proceeds in due order, when, though the wicked are bound by the fetters of sin, he lays down the law in his promises, that he will do them good only if they depart from their wickedness. This would be right, though His only object were to let them understand that they are deservedly excluded from the favour due to his true worshipers. On the other hand, as he desires by all means to stir up believers to supplicate his grace, it surely should not seem strange that he attempts to accomplish by promises the same thing which, as we have shown, he to their great benefit accomplishes by means of precepts. Being taught by precepts what the will of God is, we are reminded of our wretchedness in being so completely at variance with that will, and, at the same time, are stimulated to invoke the aid of the Spirit to guide us into the right path. But as our indolence is not sufficiently aroused by precepts, promises are added, that they may attract us by their sweetness, and produce a feeling of love for the precept. The greater our desire of righteousness, the greater will be our earnestness to obtain the grace of God. And thus it is, that in the protestations, "if we be willing", "if thou shalt hearken", the Lord neither attributes to us a full power of willing and hearkening, nor yet mocks us for our impotence.

11. The third class of objections is not unlike the other two. For they produce passages in which God upbraids his people for their ingratitude, intimating that it was not his fault that they did not obtain all kinds of favour from his indulgence. Of such passages, the following are examples: "The Amalekites and the Canaanites are before you, and ye shall fall by the sword: because ye are turned away from the Lord, therefore the Lord will not be with you," (Num 14:43.) "Because ye have done all these works, saith the Lord, and I spake unto yo u, rising up early and speaking, but ye heard not; and I called you, but ye answered not; therefore will I do unto this house, which is called by my name, wherein ye trust, and unto the place which I gave to you and to your fathers, as I have done to Shiloh," (Jer 7:13,14.) "They obeyed not thy voice, neither walked in thy law; they have done nothing of all that thou commandedst them to do: therefore thou hast caused all this evil to come upon them," (Jer 32:23.) How, they ask, can such upbraiding be directed against those who have it in their power immediately to reply, - Prosperity was dear to us: we feared adversity; that we did not, in order to obtain the one and avoid the other, obey the Lord, and listen to his voice, is owing to its not being free for us to do so in consequence of our subjection to the dominion of sin; in vain, therefore, are we upbraided with evils which it was not in our power to escape. But to say nothing of the pretext of necessity, which is but a feeble and flimsy defence of their conduct, can they, I ask, deny their guilt? If they are held convicted of any fault, the Lord is not unjust in upbraiding them for having, by their own perverseness, deprived themselves of the advantages of his kindness. Let them say, then, whether they can deny that their own will is the depraved cause of their rebellion. If they find within themselves a fountain of wickedness, why do they stand declaiming about extraneous causes, with the view of making it appear that they are not the authors of their own destruction? If it be true that it is not for another's faults that sinners are both deprived of the divine favour, and visited with punishment, there is good reason why they should hear these rebukes from the mouth of God. If they obstinately persist in their vices, let them learn in their calamities to accuse and detest their own wickedness, instead of charging God with cruelty and injustice. If they have not manifested docility, let them, under a feeling of disgust at the sins which they see to be the cause of their misery and ruin, return to the right path, and, with serious contrition, confess the very thing of which the Lord by his rebuke reminds them. Of what use those upbraidings of the prophets above quoted are to believers, appears from the solemn prayer of Daniel, as given in his ninth chapter. Of their use in regard to the ungodly, we see an example in the Jews, to whom Jeremiah was ordered to explain the cause of their miseries, though the event could not be otherwise than the Lord had foretold. "Therefore thou shalt speak these words unto them; but they will not hearken unto thee: thou shalt also call unto them; but they will not answer thee," (Jer 7:27.) Of what use, then, was it to talk to the deaf? It was, that even against their will they might understand that what they heard was true, and that it was impious blasphemy to transfer the blame of their wickedness to God, when it resided in themselves. These few explanations will make it very easy for the reader to disentangle himself from the immense heap of passages (containing both precepts and reprimands) which the enemies of divine grace are in the habit of piling up, that they may thereon erect their statue of free will. The Psalmist upbraids the Jews as "a stubborn and rebellious generation; a generation that set not their heart aright," (Psalms 78:8;) and in another passage, he exhorts the men of his time, "Harden not your heart," (Psalms 95:8.) This implies that the whole blame of the rebellion lies in human depravity. But it is foolish thence to infer, that the heart, the preparation of which is from the Lord, may be equally bent in either direction. The Psalmist says, "I have inclined my heart to perform thy statutes alway," (Psalms 119:112;) meaning, that with willing and cheerful readiness of mind he had devoted himself to God. He does not boast, however, that he was the author of that disposition, for in the same psalm he acknowledges it to be the gift of God. We must, therefore, attend to the admonition of Paul, when he thus addresses believers, "Work out your own salvation with fear and trembling. For it is God which worketh in you both to will and to do of his good pleasure," (Philippians 2:12,13.) He ascribes to them a part in acting that they may not indulge in carnal sloth, but by enjoining fear and trembling, he humbles them so as to keep them in remembrance, that the very thing which they are ordered to do is the proper work of God - distinctly intimating, that believers act (if I may so speak) passively in as much as the power is given them from heaven, and cannot in any way be arrogated to themselves. Accordingly, when Peter exhorts us to "add to faith virtue," (2Pe 1:5,) he does not concede to us the possession of a second place, as if we could do anything separately. He only arouses the sluggishness of our flesh, by which faith itself is frequently stifled. To the same effect are the words of Paul. He says, "Quench not the Spirit," (1Th 5:19;) because a spirit of sloth, if not guarded against, is ever and anon creeping in upon believers. But should any thence infer that it is entirely in their own power to foster the offered light, his ignorance will easily be refuted by the fact, that the very diligence which Paul enjoins is derived only from God, (2Co 7:1.) We are often commanded to purge ourselves of all impurity, though the Spirit claims this as his peculiar office. In fine, that what properly belongs to God is transferred to us only by way of concession, is plain from the words of John, "He that is begotten of God keepeth himself," (1 John 5:18.) The advocates of free will fasten upon the expression as if it implied, that we are kept partly by the power of God, partly by our own, whereas the very keeping of which the Apostle speaks is itself from heaven. Hence, Christ prays his Father to keep us from evil, (John 17:15,) and we know that believers, in their warfare against Satan, owe their victory to the armour of God. Accordingly, Peter, after saying, "Ye have purified your souls in obeying the truth," immediately adds by way of correction, "through the Spirit," (1Pe 1:22.) In fine, the nothingness of human strength in the spiritual contest is briefly shown by John, when he says, that "Whosoever is born of God does not commit sin; for his seed remaineth in him" (1 John 3:9.) He elsewhere gives the reasons "This is the victory that overcometh the world, even our faith," (1 John 5:4.)

12. But a passage is produced from the Law of Moses, which seems very adverse to the view now given. After promulgating the Law, he takes the people to witness in these terms: "This commandment which I command thee this day, it is not hidden from thee, neither is it far off. It is not in heaven, that thou shouldest say, Who shall go up for us to heaven, and bring it unto us, that we may hear it, and do it? But the word is very nigh unto thee, in thy mouth, and in thy heart, that thou mayest do it," (Deu 30:11,12,14.) Certainly, if this is to be understood of mere precepts, I admit that it is of no little importance to the matter in hand. For, though it were easy to evade the difficulty by saying, that the thing here treated of is not the observance of the law, but the facility and readiness of becoming acquainted with it, some scruple, perhaps, would still remain. The Apostle Paul, however, no mean interpreter, removes all doubt when he affirms, that Moses here spoke of the doctrine of the Gospel, (Rom 10:8.) If any one is so refractory as to contend that Paul violently wrested the words in applying them to the Gospel, though his hardihood is chargeable with impiety, we are still able, independently of the authority of the Apostle, to repel the objection. For, if Moses spoke of precepts merely, he was only inflating the people with vain confidence. Had they attempted the observance of the law in their own strength, as a matter in which they should find no difficulty, what else could have been the result than to throw them headlong? Where, then, was that easy means of observing the law, when the only access to it was over a fatal precipice? Accordingly, nothing is more certain than that under these words is comprehended the covenant of mercy, which had been promulgated along with the demands of the law. A few verses before, he had said, "The Lord thy God will circumcise thine heart, and the heart of thy seed, to love the Lord thy God with all thine heart, and with all thy soul, that thou mayest live," (Deu 30:6.) Therefore, the readiness of which he immediately after speaks was placed not in the power of man, but in the protection and help of the Holy Spirit, who mightily performs his own work in our weakness. The passage, however, is not to be understood of precepts simply, but rather of the Gospel promises, which, so far from proving any power in us to fulfil righteousness, utterly disprove it. This is confirmed by the testimony of Paul, when he observes that the Gospel holds forth salvation to us, not under the harsh arduous, and impossible terms on which the law treats with us, (namely, that those shall obtain it who fulfil all its demands,) but on terms easy, expeditious, and readily obtained. This passage, therefore, tends in no degree to establish the freedom of the human will.

13. They are wont also to adduce certain passages in which God is said occasionally to try men, by withdrawing the assistance of his grace, and to wait until they turn to him, as in Hosea, "I will go and return to my place, till they acknowledge their offence, and seek my face," (Hosea 5:15.) It were absurd, (say they,) that the Lord should wait till Israel should seek his face, if their minds were not flexible, so as to turn in either direction of their own accord. As if anything were more common in the prophetical writings than for God to put on the semblance of rejecting and casting off his people until they reform their lives. But what can our opponents extract from such threats? If they mean to maintain that a people, when abandoned by God, are able of themselves to think of turning unto him, they will do it in the very face of Scripture. On the other hand, if they admit that divine grace is necessary to conversion, why do they dispute with us? But while they admit that grace is so far necessary, they insist on reserving some ability for man. How do they prove it? Certainly not from this nor any similar passage; for it is one thing to withdraw from man, and look to what he will do when thus abandoned and left to himself, and another thing to assist his powers, (whatever they may be,) in proportion to their weakness. What, then, it will be asked, is meant by such expressions? I answer, just the same as if God were to say, Since nothing is gained by admonishing, exhorting, rebuking this stubborn people, I will withdraw for a little, and silently leave them to be afflicted; I shall see whether, after long calamity, any remembrance of me will return, and induce them to seek my face. But by the departure of the Lord to a distance is meant the withdrawal of prophecy. By his waiting to see what men will do is meant that he, while silent, and in a manner hiding himself, tries them for a season with various afflictions. Both he does that he may humble us the more; for we shall sooner be broken than corrected by the strokes of adversity, unless his Spirit train us to docility. Moreover, when the Lord, offended and, as it were, fatigued with our obstinate perverseness, leaves us for a while, (by withdrawing his word, in which he is wont in some degree to manifest his presence,) and makes trial of what we will do in his absence, from this it is erroneously inferred, that there is some power of free will, the extent of which is to be considered and tried, whereas the only end which he has in view is to bring us to an acknowledgement of our utter nothingness.

14. Another objection is founded on a mode of speaking which is constantly observed both in Scripture and in common discourse. God works are said to be ours, and we are said to do what is holy and acceptable to God, just as we are said to commit sin. But if sins are justly imputed to us, as proceeding from ourselves, for the same reason (say they) some share must certainly be attributed to us in works of righteousness. It could not be accordant with reason to say, that we do those things which we are incapable of doing of our own motion, God moving us, as if we were stones. These expressions, therefore, it is said, indicate that while, in the matter of grace, we give the first place to God, a secondary place must be assigned to our agency. If the only thing here insisted on were, that good works are termed ours, I, in my turn, would reply, that the bread which we ask God to give us is also termed ours. What, then, can be inferred from the title of possession, but simply that, by the kindness and free gift of Gods that becomes ours which in other respects is by no means due to us? Therefore let them either ridicule the same absurdity in the Lord's Prayer, or let them cease to regard it as absurd, that good works should be called ours, though our only property in them is derived from the liberality of God. But there is something stronger in the fact, that we are often said in Scripture to worship God, do justice, obey the law, and follow good works. These being proper offices of the mind and will, how can they be consistently referred to the Spirit, and, at the same time, attributed to us, unless there be some concurrence on our part with the divine agency? This difficulty will be easily disposed of if we attend to the manner in which the Holy Spirit acts in the righteous. The similitude with which they invidiously assail us is foreign to the purpose; for who is so absurd as to imagine that movement in man differs in nothing from the impulse given to a stone? Nor can anything of the kind be inferred from our doctrine. To the natural powers of man we ascribe approving and rejecting, willing and not willing, striving and resisting, viz., approving vanity, rejecting solid good, willing evil and not willing good, striving for wickedness and resisting righteousness. What then does the Lord do? If he sees meet to employ depravity of this description as an instrument of his anger, he gives it whatever aim and direction he pleases, that, by a guilty hand, he may accomplish his own good work. A wicked man thus serving the power of God, while he is bent only on following his own lust, can we compare to a stone, which, driven by an external impulse, is borne along without motion, or sense, or will of its own? We see how wide the difference is. But how stands the case with the godly, as to whom chiefly the question is raised? When God erects his kingdom in them, he, by means of his Spirit, curbs their will, that it may not follow its natural bent, and be carried hither and thither by vagrant lusts; bends, frames trains, and guides it according to the rule of his justice, so as to incline it to righteousness and holiness, and establishes and strengthens it by the energy of his Spirit, that it may not stumble or fall. For which reason Augustine thus expresses himself, (De Corrept. et Gratia, cap. 2,) "It will be said we are therefore acted upon, and do not act. Nay, you act and are acted upon, and you then act well when you are acted upon by one that is good. The Spirit of God who actuates you is your helper in acting, and bears the name of helper, because you, too, do something." In the former member of this sentence, he reminds us that the agency of man is not destroyed by the motion of the Holy Spirit, because nature furnishes the will which is guided so as to aspire to good. As to the second member of the sentence, in which he says that the very idea of help implies that we also do something, we must not understand it as if he were attributing to us some independent power of action; but not to foster a feeling of sloth, he reconciles the agency of God with our own agency, by saying, that to wish is from nature, to wish well is from grace. Accordingly, he had said a little before, "Did not God assist us, we should not only not be able to conquer, but not able even to fight."

15. Hence it appears that the grace of God (as this name is used when regeneration is spoken of) is the rule of the Spirit, in directing and governing the human will. Govern he cannot, without correcting, reforming, renovating, (hence we say that the beginning of regeneration consists in the abolition of what is ours;) in like manner, he cannot govern without moving, impelling, urging, and restraining. Accordingly, all the actions which are afterwards done are truly said to be wholly his. Meanwhile, we deny not the truth of Augustine's doctrine, that the will is not destroyed, but rather repaired, by grace - the two things being perfectly consistent, viz., that the human will may be said to be renewed when its vitiosity and perverseness being corrected, it is conformed to the true standard of righteousness and that, at the same time, the will may be said to be made new, being so vitiated and corrupted that its nature must be entirely changed. There is nothing then to prevent us from saying, that our will does what the Spirit does in us, although the will contributes nothing of itself apart from grace. We must, therefore, remember what we quoted from Augustine, that some men labour in vain to find in the human will some good quality properly belonging to it. Any intermixture which men attempt to make by conjoining the effort of their own will with divine grace is corruption, just as when unwholesome and muddy water is used to dilute wine. But though every thing good in the will is entirely derived from the influence of the Spirit, yet, because we have naturally an innate power of willing, we are not improperly said to do the things of which God claims for himself all the praise; first, because every thing which his kindness produces in us is our own, (only we must understand that it is not of ourselves;) and, secondly, because it is our mind, our will, our study which are guided by him to what is good.

16. The other passages which they gather together from different quarters will not give much trouble to any person of tolerable understanding, who pays due attention to the explanations already given. They adduce the passage of Genesis, "Unto thee shall be his desire, and thou shalt rule over him," (Gen 4:7.) This they interpret of sin, as if the Lord were promising Cain that the dominion of sin should not prevail over his mind, if he would labour in subduing it. We, however, maintain that it is much more agreeable to the context to understand the words as referring to Abel, it being there the purpose of God to point out the injustice of the envy which Cain had conceived against his brother. And this He does in two ways, by showing, first, that it was vain to think he could, by means of wickedness, surpass his brother in the favour of God, by whom nothing is esteemed but righteousness; and, secondly, how ungrateful he was for the kindness he had already received, in not being able to bear with a brother who had been subjected to his authority. But lest it should be thought that we embrace this interpretation because the other is contrary to our view, let us grant that God does here speak of sin. If so, his words contain either an order or a promise. If an order, we have already demonstrated that this is no proof of man's ability; if a promise, where is the fulfilment of the promise when Cain yielded to the sin over which he ought to have prevailed? They will allege a tacit condition in the promise, as if it were said that he would gain the victory if he contended. This subterfuge is altogether unavailing. For, if the dominion spoken of refers to sin, no man can have any doubt that the form of expression is imperative, declaring not what we are able, but what it is our duty to do, even if beyond our ability. Although both the nature of the case, and the rule of grammatical construction, require that it be regarded as a comparison between Cain and Abel, we think the only preference given to the younger brother was, that the elder made himself inferior by his own wickedness. 17. They appeal, moreover, to the testimony of the Apostle Paul, because he says, "It is not of him that willeth, nor of him that runneth, but of God that showeth mercy," (Rom 9:15.) From this they infer, that there is something in will and endeavour, which, though weak in themselves, still, being mercifully aided by God, are not without some measure of success. But if they would attend in sober earnest to the subject there handled by Paul, they would not so rashly pervert his meaning. I am aware they can quote Origin and Jerome in support of this exposition. To these I might, in my turn, oppose Augustine. But it is of no consequence what they thought, if it is clear what Paul meant. He teaches that salvation is prepared for those only on whom the Lord is pleased to bestow his mercy - that ruin and death await all whom he has not chosen. He had proved the cond ition of the reprobate by the example of Pharaoh, and confirmed the certainty of gratuitous election by the passage in Moses, "I will have mercy on whom I will have mercy." Thereafter he concludes, that it is not of him that willeth, nor of him that runneth, but of God that showeth mercy. If these words are understood to mean that the will or endeavour are not sufficient, because unequal to such a task, the Apostle has not used them very appropriately. We must therefore abandon this absurd mode of arguing, "It is not of him that willeth, nor of him that runneth;" therefore, there is some will, some running. Paul's meaning is more simple - there is no will nor running by which we can prepare the way for our salvation - it is wholly of the divine mercy. He indeed says nothing more than he says to Titus, when he writes, "After that the kindness and love of God our Saviour toward man appeared, not by works of righteousness which we have done, but according to his mercy he saved us," (Titus 3:4,5.) Those who argue that Paul insinuated there was some will and some running when he said, "It is not of him that willeth, nor of him that runneth," would not allow me to argue after the same fashion, that we have done some righteous works, because Paul says that we have attained the divine favour, "not by works of righteousness which we have done." But if they see a flaw in this mode of arguing, let them open their eyes, and they will see that their own mode is not free from a similar fallacy. The argument which Augustine uses is well founded, "If it is said, 'It is not of him that willeth, nor of him that runneth,' because neither will nor running are sufficient; it may, on the other hand, be retorted, it is not 'of God that showeth mercy,' because mercy does not act alone," (August. Ep. 170, ad Vital. See also Enchirid. ad Laurent. cap. 32.) This second proposition being absurd, Augustine justly concludes the meaning of the words to be, that there is no good will in man until it is prepared by the Lord; not that we ought not to will and run, but that both are produced in us by God. Some, with equal unskilfulness, wrest the saying of Paul, "We are labourers together with God," (1Co 3:9.) There cannot be a doubt that these words apply to ministers only, who are called "labourers with God," not from bringing any thing of their own, but because God makes use of their instrumentality after he has rendered them fit, and provided them with the necessary endowments.

18. They appeal also to Ecclesiasticus, who is well known to be a writer of doubtful authority. But, though we might justly decline his testimony, let us see what he says in support of free will. His words are, "He himself made man from the beginning, and left him in the hand of his counsel; If thou wilt, to keep the commandments, and perform acceptable faithfulness. He has set fire and water before thee: stretch forth thy hand unto whether thou wilt. Before man is life and death; and whether him liketh shall be given him," (Ecclesiasticus 15:14-17.) Grant that man received at his creation a power of acquiring life or death; what, then, if we, on the other hand, can reply that he has lost it? Assuredly I have no intention to contradict Solomon, who asserts that "God has made man upright;" that "they have sought out many inventions," (Ecclesiastes 7:29.) But since man, by degenerating, has made shipwreck of himself and all his blessings, it certainly does not follow, that every thing attributed to his nature, as originally constituted, applies to it now when vitiated and degenerate. Therefore, not only to my opponents, but to the author of Ecclesiasticus himself, (whoever he may have been,) this is my answer: If you mean to tell man that in himself there is a power of acquiring salvation, your authority with us is not so great as, in the least degree, to prejudice the undoubted word of God; but if only wishing to curb the malignity of the fleshy which by transferring the blame of its own wickedness to God, is wont to catch at a vain defence, you say that rectitude was given to man, in order to make it apparent he was the cause of his own destruction, I willingly assent. Only agree with me in this, that it is by his own fault he is stript of the ornaments in which the Lord at first attired him, and then let us unite in acknowledging that what he now wants is a physician, and not a defender.

19. There is nothing more frequent in their mouths than the parable of the traveller who fell among thieves, and was left half dead, (Luke 10:32.) I am aware that it is a common idea with almost all writers, that under the figure of the traveller is represented the calamity of the human race. Hence our opponents argue that man was not so mutilated by the robbery of sin and the devil as not to preserve some remains of his former endowments; because it is said he was left half dead. For where is the half living, unless some portion of right will and reason remain? First, were I to deny that there is any room for their allegory, what could they say? There can be no doubt that the Fathers invented it contrary to the genuine sense of the parable. Allegories ought to be carried no further than Scripture expressly sanctions: so far are they from forming a sufficient basis to found doctrines upon. And were I so disposed I might easily find the means of tearing up this fiction by the roots. The Word of God leaves no half life to man, but teaches, that, in regard to life and happiness, he has utterly perished. Paul, when he speaks of our redemption, says not that the half dead are cured (Eph 2:5; 5:14) but that those who were dead are raised up. He does not call upon the half dead to receive the illumination of Christ, but upon those who are asleep and buried. In the same way our Lord himself says, "The hour is coming, and now is, when the dead sha ll hear the voice of the Son of God," (John 5:25.) How can they presume to set up a flimsy allegory in opposition to so many clear statements? But be it that this allegory is good evidence, what can they extort out of it? Man is half dead, therefore there is some soundness in him. True! he has a mind capable of understanding, though incapable of attaining to heavenly and spiritual wisdom; he has some discernment of what is honourable; he has some sense of the Divinity, though he cannot reach the true knowledge of God. But to what do these amount? They certainly do not refute the doctrine of Augustine - a doctrine confirmed by the common suffrages even of the Schoolmen, that after the fall, the free gifts on which salvation depends were withdrawn, and natural gifts corrupted and defiled, (supra, chap. 2 sec. 2.) Let it stand, therefore, as an indubitable truth, which no engines can shake, that the mind of man is so entirely alienated from the righteousness of God that he cannot conceive, desire, or design any thing but what is wicked, distorted, foul, impure, and iniquitous; that his heart is so thoroughly envenomed by sin that it can breathe out nothing but corruption and rottenness; that if some men occasionally make a show of goodness, their mind is ever interwoven with hypocrisy and deceit, their soul inwardly bound with the fetters of wickedness.

John Calvin, "Institutes of the Christian Religion"

https://www.monergism.com/

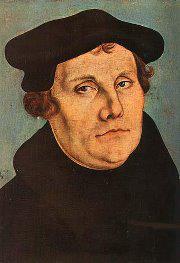

The very name, Free-will, was odious to all the Fathers. I, for my part, admit that God gave to mankind a free will, but the question is, whether this same freedom be in our power and strength, or no? We may very fitly call it a subverted, perverse, fickle, and wavering will, for it is only God that works in us, and we must suffer and be subject to his pleasure. Even as a potter out of his clay makes a pot or vessel, so he wills, so it is for our free will, to suffer and not to work. It stands not in our strength; for we are not able to do anything that is good in divine matters.

The very name, Free-will, was odious to all the Fathers. I, for my part, admit that God gave to mankind a free will, but the question is, whether this same freedom be in our power and strength, or no? We may very fitly call it a subverted, perverse, fickle, and wavering will, for it is only God that works in us, and we must suffer and be subject to his pleasure. Even as a potter out of his clay makes a pot or vessel, so he wills, so it is for our free will, to suffer and not to work. It stands not in our strength; for we are not able to do anything that is good in divine matters.